“The Mobile Schools initiative makes the entire computer lab and library mobile and independent of local infrastructure, and travels to villages at a relatively low cost.”

ALEKSANDRA VUJIC

Member of Sri Madhavananda World Peace Council, Vienna, Austria, and the Australian Association Yoga in Daily Life, a non-governmental organization in consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council and associated with the UN Department of Public Information

The right to education is a fundamental human right, since it is a precondition for the fulfilment of other economic, social, cultural, civil, and political rights. It enables social mobility and successful competition in the labour market. Its realization means overcoming poverty and living with human dignity. Being universal, interdependent, interrelated, and indivisible, the right to an education offers equal opportunities for all, regardless of gender, economic or social status.

The right to education is a fundamental human right, since it is a precondition for the fulfilment of other economic, social, cultural, civil, and political rights. It enables social mobility and successful competition in the labour market. Its realization means overcoming poverty and living with human dignity. Being universal, interdependent, interrelated, and indivisible, the right to an education offers equal opportunities for all, regardless of gender, economic or social status.

The first attempt to promote the right to education was Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, while the Convention against Discrimination in Education, adopted by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1960, and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) were the first legally binding international instruments to incorporate the wide range of this right. Article 13 of CESCR obliged United Nations Member States to recognize the right to free, compulsory primary education available to everyone, accessible secondary education, and equally accessible higher education. It pledged states to develop a system of schools for all levels, to establish an adequate fellowship system, and to continually improve material conditions for teaching staff.

After sixty years, the UN Millennium Declaration called for States to ensure that children everywhere, boys and girls alike, would be able to complete a full course of primary education. Yet statistical data from 2007 indicated that “one sixth of the world’s population, approximately 760 million persons, cannot read or write.”1

It was noted that rural children were twice as likely to be out of school as children living in urban areas and that “the rural-urban gap particularly affects the education of girls.”2 Considering the fact that many children leave school without adequate literacy, numeracy or without possessing basic life skills, Goal 2 of the Education for All initiative led by UNESCO called for good quality primary education, and Goal 6, for improving all aspects of the quality of education and ensuring excellence for all, so that recognized and measurable learning outcomes are achieved by all.

It becomes obvious that realizing the right to education, in particular a good quality education, is a global issue demanding global responses and the joint efforts of states, policy makers and civil society. The question is, is it possible to share the advancements of the twenty-first century in education with all? Rare examples have shown that it is.

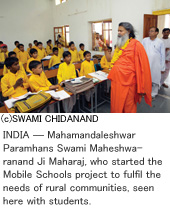

The Gyan Putra project in India, which supports Millennium Development Goal 2 on achieving universal primary education, is being undertaken in Jadan, Pali District, western Rajasthan, under the umbrella of the worldwide Yoga in Daily Life societies and inspired by Mahamandaleshwar Paramhans Swami Maheshwaranand Ji Maharaj. Employing well-trained, qualified teachers in primary and secondary school, it comprises 53 modern classrooms equipped with computers, science laboratories, state-of-the-art sports facilities as well as a well-equipped library. The project acknowledges the need for rural and marginalized students to not just avail of free education, but to have a standard of education equivalent to that which is available to students from more privileged backgrounds. Students without financial means, including all female students, study free of charge and get free transportation, uniforms, books, and stationery arranged by the school.

Despite low educational achievements, high dropout rates, and no provision for information technology education and library facilities in rural and backward areas, Yoga in Daily Life intends to spread its activities to twenty-seven villages through the Mobile Schools initiative in village schools up to the eighth grade. The Mobile Schools initiative makes the entire computer lab and library mobile and independent of local infrastructure, and travels to villages at a relatively low cost. The highlights of the initiative are:

- The use of laptops, charged during the evening at a central location with 24 hour power supply, removes electricity constraints and gives students a chance to fulfil and aspire to greater self-learning platforms through information and communication technologies (ICT).

- By accessing software and learning programmes from the organization’s world network, the labs can offer high quality, modern learning materials to students targeting specific learning objectives.

- Quality education and excellent learning outcomes, especially in literacy, numeracy, and essential life skills, are obtained by a holistic programme in which ICTs are used in tandem with library and reading programmes.

- The use of media such as photography and video makes it possible for students to learn about their surroundings, hygiene, personal development, and relationships.

- High quality teaching staff with excellent classroom instruction and training improve the learning experience.

- Teaching staff, combining experts in the field with local assistants, bring the syllabus “on the ground,” increasing its relevance by giving it local context.

- Teachers are trained to deal appropriately with gender issues and encourage girls to participate and aspire to education levels equal to those of boys, and vice versa.

- Girl students are given quality, modern education in the vicinity of their homes, in a safe environment. Access, safety, social integration and future benefits of any type of education are primary issues which affect parents’ decisions to educate their girls in the rural setting.

- By offering a modern, stimulating and socially relevant education experience, children will be motivated to complete a full course of primary schooling and continue their schooling in higher grades.

The Mobile Schools initiative is an exciting, simple, and effective way of improving the educational outcomes of those most in need. It is the way to bring quality education to the most isolated villages, to utilize current infrastructure, and to establish a partnership between government schools and civil society. It is a tool for improving attendance in schools in a village setting and convincing parents an education will bring tangible changes in quality of life and open new avenues for the students in the future. Giving marginalized rural students standards of education equivalent to city schools while maintaining the rural context will increase outcomes and school attendance and promote personal development.

The Mobile Schools project is a practical, viable, and economical way to fulfil the needs of rural communities, paving the way for the fulfilment of the Millennium Development Goals. It is the way to meet the concerns voiced by Heads of State in the Doha Declaration that the current financial crisis and global economic slowdown could jeopardize the fulfilment of the MDGs, especially the needs of the poorest and most vulnerable. It demonstrates how existing capacities and resources in civil society can be explored and used to the maximum.

Most importantly, the Mobile Schools initiative can be implemented and is sustainable in all geographic locations. It is a model for increasing enrolment, narrowing gender gaps, and extending opportunities for disadvantaged groups in education.

- The United Nations Academic Impact

- Education for All: Rising to the Challenge

- Preparing the Next Generation to Join the Conference Table

- Unlearning Intolerence through Education

- Can Education Be Made Mobile?

- National Identity and Minority Languages

- Education as a Means to Promote Sustainability

- Academic Impact and Education for Sustainable Development: The Contribution of Black Sea Region Universities

- Reducing Poverty Through Education – and How

- SimplyHelp Cambodia: A Vocational Education Mode of Success

- Civic Education and Inclusion: A Market or a Public Interest Perspective?

- Who Speaks for the Poor, And Why Does it Matter?